What You Need To Know, 2026

The attic plays a crucial role in your home’s performance year-round. Proper insulation and ventilation can significantly improve comfort and efficiency, giving you peace of mind. When an attic isn’t functioning correctly, it can lead to heat loss, ice dams, and moisture problems, but these issues are manageable with the right approach.

What an inspector often finds in the attic

A professional attic inspection routinely reveals issues that homeowners are unaware of. Insulation that appears consistent from below may be uneven, shallow or missing in key areas once an inspector enters the attic. Around attic hatches, plumbing stacks, chimneys, and older recessed fixtures, warm air often escapes into the attic through small openings in the ceiling plane.

White cellulose insulation with insufficient depth for the attic structure, a common issue in older homes.

Attic insulation depth

Insulation levels vary widely across homes in Kingston and the Area. Many older properties, especially those built before the mid-1990s, have insulation that falls well short of current standards. In these homes, it is common to find only R20 or R32 insulation, sometimes with material that has settled, compressed, or shifted over the years. Thin coverage near the eaves is widespread, and past renovations or electrical work may have left small, hidden bare areas.

Blown-in insulation helps older homes reach modern R-values for comfort and energy efficiency—image source: Home Depot Canada.

Today’s recommended levels are far higher. Attic insulation between R50 and R60 provides much better protection during the winter months. Homes with modern insulation levels retain heat more effectively, reduce warm-air infiltration into the attic, and lower the risk of ice dams. During the summer, deeper insulation helps prevent heat from entering the living areas, creating more stable indoor temperatures and reducing the load on air conditioning systems.

Inspectors pay close attention to insulation depth because even one small gap can create a warm path into the attic. These warm paths often lead to frost on sheathing, uneven snowmelt on the roof, and moisture problems that grow slowly over time.

See Also- Home Depot: How to Insulate Your Attic Guide

Local Attic Insulation Types

Attics in our area contain a wide range of materials, each installed during a different era of construction and renovation.

Batt insulation made of fibreglass or mineral wool appears commonly in homes built after the 1970s. It can perform well when consistent, but it is easily disturbed by wildlife or previous renovation work. Blown-in cellulose is also widespread, particularly in older homes that were retrofitted during the energy-efficiency programs of the 1970s and early 1980s. It provides good coverage at first but tends to settle over time. Blown-in fibreglass is a common retrofit choice today because it resists moisture and settles far less.

Spray foam insulation is most commonly used in basement rim joists, wall cavities and other areas where air sealing is critical. It now appears more often in attics during major renovations or energy-efficiency upgrades. When installed correctly, spray foam provides a high R-value and creates an effective air seal, although its use in attics remains less common than batt or blown-in insulation.

Vermiculite insulation

Vermiculite insulation was widely used in Ontario from the 1940s through the mid-1980s. Its peak installation period was in homes built between the 1920s and the 1960s, and its use increased again during the 1970s energy crisis. By the mid-1980s, awareness of asbestos contamination led to its use declining and then stopping entirely. By the late 1980s, asbestos-containing products were banned in Ontario.

Zonolite attic insulation was widely used in Ontario from the 1940s to the mid-1980s. Some batches of the material contained asbestos and should be tested before renovations.

Since vermiculite may contain asbestos, homeowners should understand the health risks and consider testing or professional removal to ensure safety.

Asbestos in other insulation?

Although vermiculite is the most widely known concern, other early loose-fill products can also be problematic. Some older grey or off-white loose fibres, sometimes historically referred to as “asbestos wool,” may contain asbestos depending on when they were manufactured. Early versions of rock wool, produced before modern standards, may also contain trace amounts of asbestos. When I encounter unidentified loose-fill insulation from an older period, testing is often recommended to help the homeowner understand the material before planning upgrades or renovations.

Avoid surprises by recognizing typical attic issues yourself, such as uneven insulation, visible frost, or animal droppings, prompting timely inspections.

A professional attic inspection routinely reveals issues that homeowners are unaware of. Insulation that appears consistent from below may be uneven, missing in corners or compressed in key areas. Around attic hatches, plumbing stacks, chimneys, and older recessed fixtures, warm air often escapes into the attic through small openings in the ceiling plane. Wildlife activity is another common issue in rural and suburban homes. Mice, squirrels and raccoons can flatten insulation, create tunnels through it and damage vapour barriers or wiring.

The Vapour Barrier

The vapour barrier itself is another critical detail. An incomplete or poorly sealed vapour barrier allows warm, moist air from the living space to enter the attic. When that air reaches the cold roof deck during winter, condensation begins. The moisture can freeze, forming frost on nails and sheathing. During warmer periods, the frost melts and drips into the insulation. This moisture reduces insulation performance, encourages mild mould growth and may eventually stain or damage the roof sheathing.

Ventilation concerns in the attic

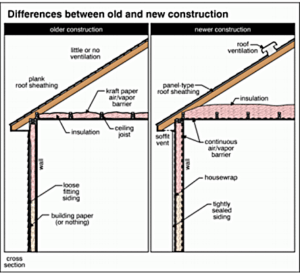

Ventilation is as important as insulation. Attics depend on a steady supply of fresh outside air entering through the soffits and warm air leaving through the ridge or roof vents. When this airflow is balanced, the attic stays dry and stable. When it is restricted, various problems arise.

One common issue is soffit vents blocked by insulation. Blockage often happens after loose-fill insulation is installed without proper baffles, or in older homes where soffit openings have been painted or covered. Without adequate intake air, the attic becomes stagnant. Temperatures rise higher than expected, moisture cannot escape, and frost may develop on cold surfaces during the winter.

Older attics often lack continuous ventilation and proper airflow, which increases the risk of moisture and heat loss.

Another issue is simply having too few vents for the attic’s size and design. Many older homes have only one or two small roof vents that cannot move enough air. Ridge vents without corresponding soffit intakes do not perform correctly. Gable vents alone often provide insufficient airflow. Homes with complex roof lines may trap warm pockets of air, even when vents are present. These ventilation shortfalls can lead to warped sheathing, musty odours, condensation and hot upper floors during the summer.

Moisture and frost concerns

Moisture poses one of the most significant risks to attic performance. When warm, humid air reaches the cold roof deck, condensation forms immediately. Over time, frost builds up on nails, rafters and sheathing. When temperatures rise, the frost melts and drips into the insulation. Wet insulation becomes heavy, loses its insulating value and may encourage mould growth on wood surfaces.

Many attic moisture problems start with improperly vented exhaust systems. Bath fans, dryers, and kitchen exhausts should all discharge to the outdoors, yet inspectors often find them discharging into the attic or just above the hatch. In some homes, the ductwork has come loose or was never connected correctly, allowing warm, humid air to escape into the attic. Over time, this moisture reaches the cold roof deck, leaving early signs such as light staining or darkened patches on the sheathing. These issues usually develop long before the homeowner realizes there is a problem.

Attic Ice dams during winter

Ice dams are a recurring issue in Kingston and Area, especially during winters with frequent freeze-thaw cycles. These dams form when heat from the home escapes into the attic, warming the underside of the roof. Snow above begins to melt, and the water flows toward the colder eaves. Once it reaches the edge, it freezes. As more water runs down, the ice grows and prevents additional meltwater from draining. Eventually, water backs up under the shingles and leaks into exterior walls or ceilings.

During an inspection, signs of ice dam activity may include uneven snow on the roof, warm, exposed patches, staining on exterior walls near the eaves, and wet insulation near the roof edges. While proper insulation and ventilation significantly reduce the risk, factors such as roof design, sun exposure and weather patterns also play a role.

Wildlife and attic disturbances

Rural and suburban homes across Eastern Ontario experience wildlife intrusion more often than homeowners expect. Mice create small tunnels through insulation, squirrels can flatten or redistribute material, and raccoons may cause structural damage as they pull away vapour barriers or destroy wiring. These disturbances reduce insulation performance and can create safety risks. Inspectors pay close attention to signs of wildlife activity because the repairs required may be more extensive than homeowners realize.

Summer performance also matters.

Although winter issues receive the most attention, attic performance is equally vital in the summer. During hot weather, the attic heats up quickly as the sun warms the roof. Without adequate insulation, this heat transfers directly into the living areas. Proper insulation helps slow this process, keeping rooms more comfortable and reducing air conditioning demands. Ventilation also plays a role by allowing hot air to escape and helping prevent excessive heat buildup that can shorten the lifespan of roofing materials.

Frequently asked questions

How much insulation should a home in Kingston and Area have?

Most homes perform best with R50 to R60 in the attic. Older homes often fall below these levels.

Can new insulation be added on top of existing insulation?

Yes. New insulation can be added, provided the existing material is not wet or mouldy. In that case, removal is necessary before upgrades.

How can I tell if my attic is adequately ventilated?

Signs of poor ventilation include warm attic temperatures during winter, musty smells, frost on nails or damp insulation. An inspector can assess soffit openings, baffles, ridge or roof vents and overall airflow.

Will upgrading the insulation eliminate ice dams?

Upgrading insulation significantly lowers the risk but does not eliminate it. Roof design, sun exposure and temperature swings also influence ice dam formation.

What happens if vermiculite is found?

Vermiculite may contain asbestos. Testing confirms this. Both removal and encapsulation are possible. Even when encapsulated, its presence must still be disclosed during a future sale.